| On return home, no

happy endings for indentured labourers By Devirupa Mitra In a small Tamil Nadu village is India’s only living link to a certain colonial past.

New York-based filmmaker Shundell Prasad Once More

Removed: You

tube More Born in Guyana, 64-year-old C.G. Naresh was a passenger on the last ship that returned home to India with indentured labourers more than five decades ago.

The

story she unveils is anchored on a crucial clause included in all

contracts forced upon mostly illiterate peasants from Bihar and Uttar

Pradesh before being shipped to work in plantations across the seven

seas. Under the “right to return” clause, the colonial government

would pay for the passage home for the labourer at the end of his

indentureship. According

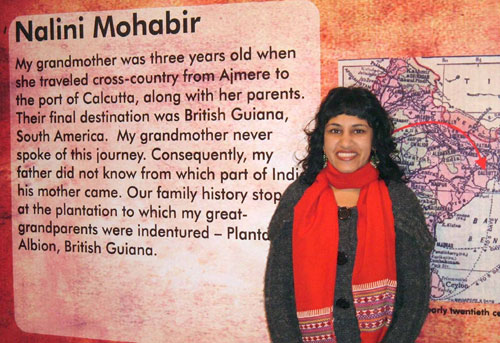

to Mohabir, who presented her research through photographs at a

diaspora festival organised by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for

Arts on the sidelines of the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas from January 8-9,

only one in four Indians who went to the colonies to work in

plantations returned home. But

the advent of Indian independence suddenly spurred the labourers, even

those who had lived there for over 60 years and had grandchildren, to

clamour to be returned back to the motherland, their visions tinted

with the glorious ideal of being part of a new Indian republic. “The

freedom movement and subsequent independence (of India) had fired the

imagination. There were protests in Trinidad and threats of mass

suicide in Jamaica over demands to return back home,” Mohabir told

IANS. Only

the government in British Guyana acquiesced and chartered a ship to

take back a thousand passengers. “But the Indian government pasted

posters around the city discouraging people to return,” she said. On

that September day 53 years ago, it seemed the entire country had come

to see off 243 passengers aboard M.V. Resurgent on Sproston’s No 1

Wharf in Georgetown. The next day’s paper summed it in a poignant

headline - “Going Home! To a home they never saw”. The

reference was to the fact that that the majority of the returnees were

going back with family, many of them having been born in the South

American colony and only knew of India from oral tales and newsreels. The

ship’s manifest lists the name and the home village, which was a

vital clue for Mohabir to trace the descendants. It

was through that method that she stumbled across the only passenger of

the ship that she could find alive - Naresh, who had travelled on

Resurgent as a 12-year-old along with 19 other family members. “His

father had sold off their entire business to return to India. But, as

soon as the ship docked at the port at Calcutta (after one month),

Naresh’s family realised that they had made a grave mistake,” said

Mohabir. Calcutta

was a strange city, already bursting at the seams with refugees from

East Pakistan and swirling with chaos due to the festival season.

Mohabir remembers that her grandfather, Chhablal Ramcharan, who

travelled with Resurgent’s passengers as the Guyanese repatriation

officer, telling her of the day after the arrival when he was besieged

at the hotel room with mob of 40 passengers. “They

were crying and pleading with him that they wanted to return back.

But, what could he do when the passage was only for one way,” she

said. Her

grandfather also told her that many of the passengers who couldn’t

remember their home villages were put up in a charity shelter called

The Refuge. That

organisation still stands at Bow Bazaar, from whose dusty ledgers she

was able to find another link to the ship. “I talked to some of the

old inmates who remembered a mother and daughter who were not from

Calcutta”. Cross checking the files of the old age home and the ship

manifest yielded two names - Manraji (in her 50s) and her daughter,

Biphia. “A

son, who had travelled with them, was not listed. Strangely, they

apparently never went to their village in Gorakhpur and stayed rest of

their lives at the Home. Manraji died sometime in the 1970s, while her

daughter was alive till the 1990s,” said Mohabir. She

found another missing link in Uttar Pradesh during her visit in the

summer of 2007 - in Amrora village in Azamgarh district was the

grandson of another passenger, Sant Sewak. “Interestingly, he did

return to his village but went back to Guyana. The grandson showed me

the letters and a will that they had preserved, complete with the

Guyanese postage stamp.” She

came across other stories of other returnees, who unable to cope with

an independent India that had changed drastically after 1947 wanted to

go back but could not afford the journey back to the colonies. “Their stories are not about India making them , January 20, 2008 |